The re-emergence of ‘Brand Canada’

Raed Ayad currently works for INTO University Partnerships as a Research and Policy Analyst. As a Canadian citizen who has studied in Canada and in the UK, he offers his reflections on the change in Government in Canada and its potential implications for Canadian international education strategy.

On October 20th, 2015 the front page of one of Canada’s leading newspapers, the Toronto Star, read ‘It’s a New Canada’, with a photo of newly-elected Prime Minister Justin Trudeau celebrating his historic win with his family and supporters.

While many, from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Victoria, British Columbia, were jubilant in celebration of their ‘New Canada,’ Prime Minister (Justin) Trudeau had a different message to the world, simply: ‘We’re back.’ Overnight, Canada seemed to reverse a decade of regression to its image, internationally.

Two months have passed since the election in which the Canadian Bureau for International Education held their annual conference in Niagara Falls and stakeholders seemed confident that this excitement would be reflected in the advancement of international higher education in Canada.

That said, according to CBIE, Canada is already home to 336,497 international students, an 84% per cent increase over the past decade. The Canadian Government is dedicated to continuing this increase, setting a goal of attracting an additional 450,000 international students and researchers by 2022. This aim of doubling international enrollment is highly attainable and already within grasp, according to talks at the CBIE conference. However, one wonders to what extent this ambitious goal might be enabled through the development of wider partnerships, especially within the context of the straitened financial circumstances which affect most of Canadian post-secondary education.

While Canada is increasing its enrollment, directly benefiting the local economy as well as the institutions, there were a number of issues raised throughout the conference. When a student studies abroad, although the academic experience is most important, it is necessary for students to gain knowledge of the customs and lifestyle of the country in order to maximize benefit. It is troubling to learn that in a survey conducted amongst 4,000 international students in Canada only 46% were reported to have a Canadian friend.

During the plenary session of the CBIE conference, Martha Navarro from the Mexican Agency for International Development Cooperation spoke of the issues faced by students who study abroad. She posed a simple question geared towards countries that attract high rates of international students, asking: who is satisfied with being tolerated?

This is a very important question for diverse cities such as Toronto, New York and London. The universities in these respective cities generally have a high percentage of international students, reflecting their high immigrant population. Integration is as essential to the world of immigration, as it is for international students. Students who leave their family, friends and comfort zone to study abroad are taking steps in developing themselves; it is up to the receiving country, its citizens and the university/college to ensure that there is a benefit for all parties involved.

Another point of discussion throughout the conference was the importance of promoting the idea of studying abroad to Canadian students. As of 2014, only 3% of Canadian students were studying abroad, one of the lowest numbers amongst OECD states. According to Karen McBride, President and CEO of CBIE; “If we don’t increase the number of students studying abroad, we won’t be involved in the trade deals that Canada is putting into place now, or in meeting global challenges.” While the Canadian strategy of doubling international enrolment in Canada is progressing well, the strategy of creating 50,000 scholarships for Canadians to study abroad has not paralleled this growth. For Canada to grow as a country, with regard to international higher education, the transfer of students and ideas must go both ways.

Public diplomacy and higher education

For Canadians, higher education is just a part of the public diplomacy measures the country must undertake to retain their place as leaders internationally. Students will always come to Canada but the success or failure of international education mustn’t be gauged by the numbers and experiences of students entering our universities, but by the numbers of international students and experiences that graduate from our universities. Additionally, the number of our own students who graduate from our international counterparts.

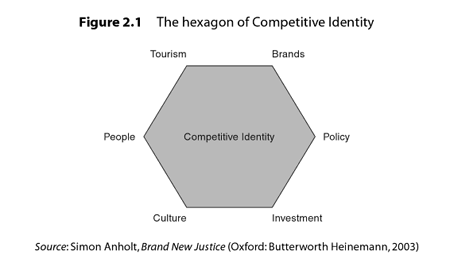

International policy advisor Simon Anholt, the champion of ‘nation branding,’ developed a hexagon of international competitive identity (pictured below), in which he defines the different determinants essential in the projection of countries internationally.

A point of benefit from developing Canada’s international higher education strategy can be made for all six determinants in the above hexagon. Starting with ‘people,’ arguably Canada’s strongest asset is their people, the general perceptions of Canadians is usually a positive one, the movement of Canadians abroad as well as the interactions with Canadians by international students should only benefit this perception. Tourism and culture go hand in hand; international students are technically ‘academic tourists’ and if they embrace the culture of Canada, they may project this to their friends as family as a friendly place worth visiting or doing business with. This leads to investment, having students study abroad, gaining knowledge of international markets will allow Canadians to play a stronger role in trade agreements and the overall global market. Finally, higher education institutions are brands and must attract students, exchange students and promote their alumni to study overseas to extend the reach of their respective brands.

“Under the leadership of Prime Minister Harper, Canada enjoyed an increase in international enrolment, albeit mainly driven by provincial, rather than federal, policy”

Since the Harper Government eliminated funding for the Understanding Canada program in 2012, the onus of projecting Canada academically has lain heavily with the institutions themselves. When the cuts were made, the Canadian Studies program had over 7,000 ‘Canadianists’ teaching students about Canada around the world in 290 centres across 50 different countries. The courses ranged from Canadian environmental and economic studies to Canadian politics and pop-culture, serving as a leading tool in public diplomacy. The Department of Foreign Affairs, Development and Trade has been provided with a new trust under Trudeau, which will allow them to re-engage with the world in order to promote both Canadian studies, as well as studying in Canada.

Under the leadership of Prime Minister Harper, Canada enjoyed an increase in international enrolment, albeit mainly driven by provincial, rather than federal, policy. Although Canada was open in welcoming students from other nations, the government did not do much to promote the public image of Canada internationally. Prime Minister Trudeau has pledged to the world that the Canada of old has returned and that his government will be dynamic and reflective of the needs of all Canadians. Similar to the manner in which the new Liberal government is attempting to be modern and innovative, the country and the provinces must do the same when developing their higher education strategies.

This post originally appeared on INTO’s corporate blog and has been reposted with the permission of the author.

Leave a Reply