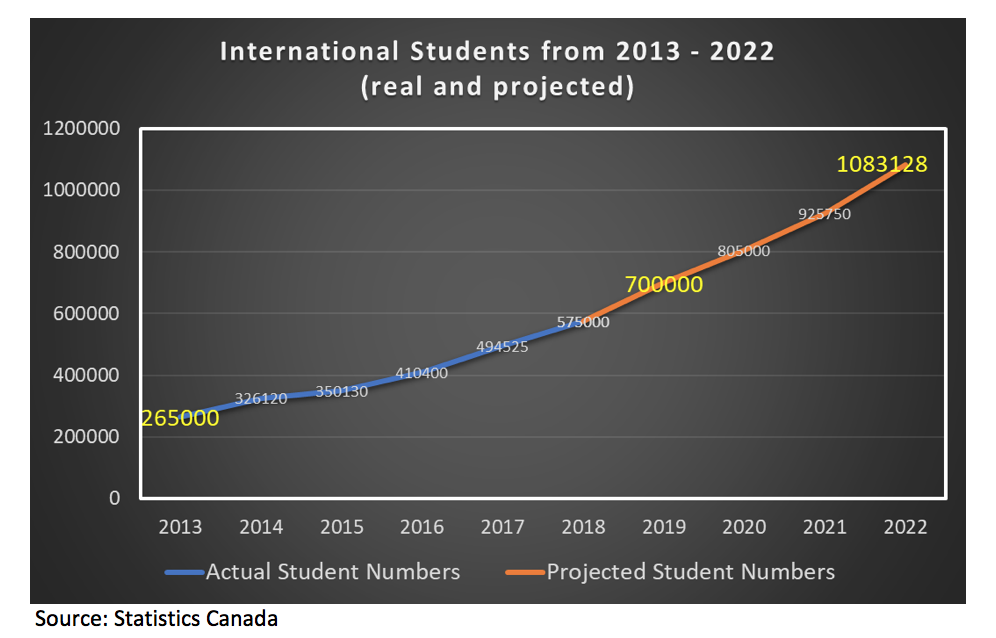

Will Canada have quadrupled its international student numbers in eight years?

“It is conceivable that Canada could have a million international students by the end of 2022”

In early 2014 the Canadian Federal Government announced its intentions to grow study permit holders in Canada from 265,000 to 450,000 and gave itself eight years. In 2017 that target was surpassed, a full five years early.

The first time I heard the goal was at a Federal Government supported student recruitment fair in Abuja, Nigeria, in late January 2014. A good number of Canadian school recruiters (myself included) were busy laying out marketing materials and preparing for the prospective students lined up outside the event. The student fair in Abuja was one stop of many throughout Africa.

Before things opened to the public, the Canadian Ambassador to Nigeria and our then-International Trade Minister (Ed Fast) took to the podium to talk new policies and give encouragement to the audience. The big takeaway? Canada’s government had identified international student growth as a major “stimulant” to the domestic economy. And the country would – in Fast’s estimation – get this injection by doubling the outcomes of our collective efforts (which were already round-the-clock). Murmurs of commentary and raised eyebrows went up. Clearly, not everyone was aligned on the scope and spirit of the proposition.

Significant Growth

Since Ed Fast’s announcement, a lot has changed. The 450,000 target was reached and surpassed in mid-2017, following two years of 15 – 17% growth. Looking at 2018 and 2019, similar compound changes continue. In 2018, Canada reached over 575,000 students on a study permit, and (according to an April 2019 seminar by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) the department indicated that there were already 700,000 current international students in Canada.

Who (or what) is Counted?

IRCC counts Study Permit Holders on December 31st of each year. This means all study permits that became effective or were valid already, in a calendar year. Notably, under Canada’s immigration regulations, not all international students in Canada require a permit. Exceptions include short-term programs (six months or less) and minor students who are alone in Canada or who have one at least one parent with working or studying status. In other words, there is a significant number studying in other sectors (K-12 and Language Schools) who are not counted in IRCC figures. If

these students transition to universities and colleges (as many intend to do) then the number will undoubtedly swell, as they activate the study permits (required by law to attend post-secondary).

Studying with the Intention to Immigrate

Canada counts education and related services as an “export”. This seems to reflect a perception that foreign students purchase goods from Canada and enrich or use the product elsewhere, as would be the case with traditional industries such as Oil and Lumber. Estimates, however, indicate that 60% of international students polled in Canada would like to remain here as immigrants (CBIE, 2018). Is the international education industry really comparable, then, to more traditional activities that move domestic goods overseas?

Understand that (since 2014 especially) Canadian federal government policy sees international students as a pool of young and well-educated potential immigrants that would mitigate against labour market shortages or a glut in population growth. In this light, in the last five years, more generous policies evidence a trend towards giving “dual intent” students an edge (whether by work rights or immigration program points). This sounds more like resource extraction.

Will Current Rates Persist?

According to Statistics Canada, there are roughly two million Canadian students in our post-secondary system. Domestic students are growing at less than 2% while international students are growing at about 15% annually. This means if international students hit the 1,000,000 mark in 2022 the cohort will comprise 30% of the student population in our colleges and universities.

Comprise this with the United States, which in 2018 had 1,090,000 and 1.5% growth. If the US numbers should recede at all, Canada will overtake the US by 2022 and Canada only has a tenth of the US population.

Another important question not being raised publicly is the international student growth compatibility with Canada’s Immigration Levels Plan. Our current 2019 – 2021 plan currently allows for about 330,000 annual permanent residency admissions with just less than half (about 150,000) set aside for ALL economic programs, which are largely skilled work or trades programs and predominantly points-based. International students in Canada are just one segment that the federal government is interested in retaining, but they are pulled from the same pool of candidates.

“If the US numbers should recede at all, Canada will overtake the US by 2022”

With 60% of 700,000 current students purportedly vying for a spot to immigrate (and limited time to bolster their scores in Canada), the odds are stacked against them at a rate of around four-to-one. This number was in line with the IRCC admission that international students who have graduated in Canada are only being retained at the rate of 25% (ICEF Vancouver Seminar, April 24th, 2019, Josée Samson-Savage, Senior Programme / Policy Advisor).

Unfortunate and disappointing a result this may be to students who will not be successful on their first attempt to immigrate to Canada, the spectre of a countless number who do not want to leave – upon expiry of their work or study permits – should be worrisome to our industry, immigration and enforcement bodies, and the labour department.

The Value of Planning for Risk

If numbers don’t persist, schools who have become dependent on this revenue for their growth may be in for a big surprise. If the numbers do persist, are our institutions properly equipped? Can the surrounding communities provide enough accommodation and employment? How will IRCC handle having more potential immigrants inside Canada that have not been given spaces? Stakeholders avoid this major question at their potential future peril.

About the author: Dave Sage is a Regulated Canadian Immigration Consultant who collaborates closely with Canadian institutions on challenges connected to the recruitment and retention of international students.

nice