Why less student mobility from China may not be the end of the world for UK education

“UK higher education institutions and their international student populations stand to lose less from the coming slowdown in Chinese outbound mobility than many may presume”

The following is an extract from the British Council’s Education in East Asia – By the Numbers report entitled ‘Why less student mobility from China may not be the end of the world for UK education’. British Council’s Services for International Education Marketing (SIEM) team helps UK institutions refine their internationalisation strategies to succeed in East Asia and around the globe. The full report is available to registered members of the British Council website here.

A recent report from the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) on global demand for English higher education has generated a great deal of attention among education practitioners and media outlets in the UK. Most coverage focused rightfully on the first net drop in international enrolment in English higher education in 29 years, as well as discussion of the various causes of this decline. With a touch of hyperbole, the Economist claimed that England’s higher education institutions were showing the world “how to ruin a global brand.”

“With a touch of hyperbole, the Economist claimed that England’s higher education institutions were showing the world ‘how to ruin a global brand'”

Given the particularly precipitous decline in new enrolments from south Asia – by upwards of 50 per cent in two years – some commenters have latched onto any good news that they can find, especially the continued rise in the number of students from China, as a bright spot for the UK sector[1]. One even proclaimed UK higher education to be “an industry winning an important share of the huge and growing Chinese market.”

But this way of thinking about China may already be outdated, as growth in China’s outbound student market has rapidly slowed. In fact, by focusing on the modest rise in overall enrolments from China, commentators overlook the surprising halt in growth at undergraduate levels in the UK in 2012/13. With students from China making up not only the largest sending market to the UK, but also the fastest growing one in recent years, this slowdown in Chinese enrolments would appear to foreshadow crisis for the UK higher education sector.

Somewhat strangely, however, UK higher education institutions and their international student populations stand to lose less from the coming slowdown in Chinese outbound mobility than many may presume. What’s more, the UK education sector is better prepared to weather a fallow period from China than any other major English speaking destination country.

Slowing dragon

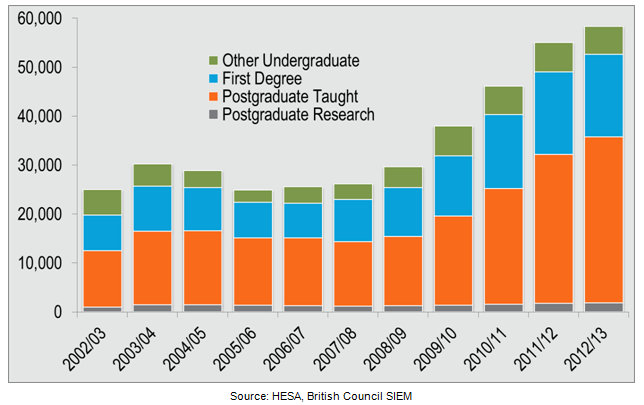

There is no doubting the outsized importance of China’s student market to the UK. China enrolled 32,000 more students in UK higher education in 2012/13 than it did only five years prior, accounting for fully 60 per cent of growth in total new enrolments of international students over this time period. Today, more than one in five international students comes from China, up from one in eight as recently as 2007/08.

“There is no doubting the outsized importance of China’s student market to the UK”

What’s more, China’s outbound student market appears at first glance to be in fine health. New enrolments in UK higher education increased by more than six per cent in 2012/13 from the year before, even as international enrolments from other countries declined[2].

Appearances can be deceiving though. The seemingly healthy bump in first-year enrolments from China in UK higher education in 2012/13 masked the slowest rate of expansion since 2007/08. Moreover, all of this growth was concentrated in postgraduate courses, with new enrolments at both undergraduate levels registering net declines. In particular, new enrolments in first-degree courses came to a halt in 2012/13 after averaging 18 per cent annual growth over the period from 2007 to 2012.

In other words, if China was the engine of growth for the UK sector from 2007/08 until 2011/12, it downshifted quite dramatically in 2012/13. And if current trends in undergraduate enrolments in the UK are a harbinger of things to come, total new enrolments could stall by as early as 2014/15, weighed down by a shrinking youth population and slowing economic growth. This will only put further pressure on UK institutions to seek new sources of international students.

But there is light at the end of the tunnel for the UK.

The tipping point

For one thing, the UK education sector is still far less dependent on Chinese enrolments than other major English language speaking countries, particularly Australia, where nearly two fifths of all international students in higher education come from China. Even when excluding EU enrolments from the international student population, the UK is less dependent on China for international enrolments than Australia, Canada or the US, meaning that the UK sector will feel the effects of a slowdown in new Chinese enrolments less than other education markets might.

While UK higher education is less reliant on China’s student market overall, some UK institutions have grown worryingly dependent on China for international enrolments in recent years. To wit, in 2002/03, there were 11 UK institutions at which first-year students from China comprised more than 30 per cent of all new international enrolments; by 2012/13, fully 30 institutions fit this profile, and two universities enrolled more Chinese students than all other international students combined… [Continue reading]

[1]While HEFCE’s report focused solely on English higher education institutions, the picture is largely the same for the entire UK sector.

[2]All statistics for UK higher education institutions come from Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA).

![Mpickett_desk[1] copy](http://blog.thepienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Mpickett_desk1-copy.jpg)