New IELTS score requirement for doctors in the UK – why so high?

“Usually you wouldn’t expect an English Teacher and a Consultant Physician to have too much in common work-wise, but that day was different”

Andy Johnson, Development Manager at The London School of English looks at the decision by the General Medical Council to revise its criteria for assessing knowledge of English amongst its members, which comes into effect this week, and the implications of these changes.

I saw a friend of mine recently who is a doctor. He’s also an Arsenal fan, though he doesn’t like to admit that at the moment! We spoke about a number of things before the conversation turned to football and eventually to work. Usually you wouldn’t expect an English Teacher and a Consultant Physician to have too much in common work-wise, but that day was different and it had nothing to do with Arsène Wenger’s team. The reason was IELTS.

The General Medical Council (GMC) announced earlier this year that from 18 June 2014, the minimum IELTS scores they accept as evidence of knowledge of English when registering doctors to work in the UK will be:

- A score of at least 7.0 in each of the four areas tested (speaking, listening, reading and writing)

- And an overall score of at least 7.5

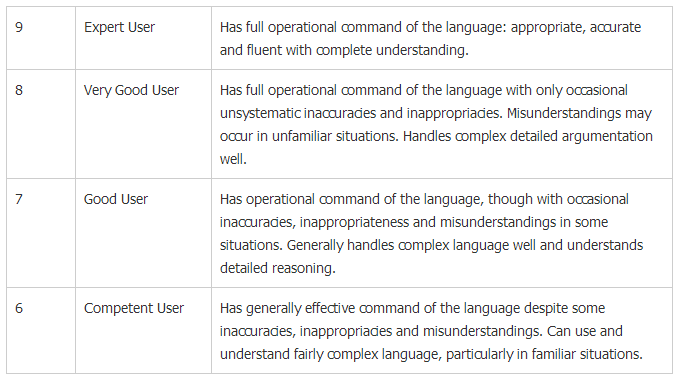

The GMC will accept only the academic version of the IELTS test. For those who are unfamiliar with the IELTS scores (ranging from 1 – 9), a score of 7.5 sits between a good, and very good user of English. Bands 6 – 9 break down as follows:

An overall score of 7.5 is a big ask. While a minimum score of 7.0 through the four modules – Listening, Reading, Writing and Speaking – seems achievable, now it is not enough. If you score 7.0 in say, speaking and writing, candidates would now need to score a minimum of 8.0 in the reading and listening papers to reach the minimum overall score. That is going to be very difficult for many candidates.

“An overall score of 7.5 is a big ask. That is going to be very difficult for many candidates”

Since these changes were announced by the GMC to its members, there has been quite an emotive response. If you take a look at the comments section on the GMC’s site, you get a sense of the depth of feeling on this topic.

Some have accused the GMC of outright discrimination, while others have warned that the UK should brace itself for a shortage of doctors in the coming months. There is an acceptance that of course a good working knowledge of English is a prerequisite to working in the UK, but this is tempered with a belief amongst members that the GMC is setting the bar too high, and that language command alone does not make you a good or bad doctor.

I cannot comment on that last point, but as a teacher with experience of the Academic module of the IELTS exam, I know how hard it is for any student to achieve an overall score of 7.5. I can understand the consternation amongst doctors and wonder if the GMC is making a rod for its own back. My friend felt the same. As a native speaker who works with many doctors for whom English is not their first language, he had a lot of sympathy with those who are going to be affected by these new requirements.

“I can understand the consternation amongst doctors and wonder if the GMC is making a rod for its own back”

The strict deadline doesn’t make things any easier. Students taking one of our intensive IELTS preparation courses often see their overall IELTS scores rise by up to one band. As with many things though, making leaps seems easier the lower the level, but the work required to keep improving becomes more difficult the higher up the scale you go.

That’s not to say that all is lost. Students can find many tips for improving their scores – for example, this blog post from The London School’s Laura, What to do in the IELTS exam, as well as practice activities on London School Online. At the school we see students scoring high on IELTS all the time.

You can hear from Malika, a former student who achieved an 8.0 in her exam here: Malika interview video.

This was originally posted on The London School’s language blog.